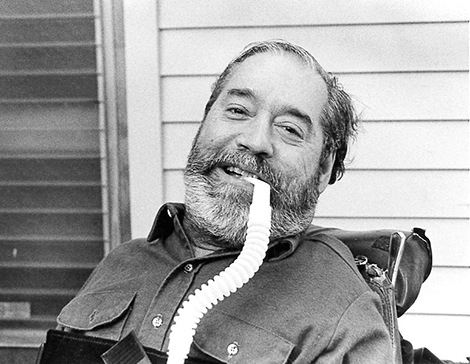

Ed Roberts is a towering figure in the history of disability rights. His advocacy challenged perceptions and created opportunities for people with disabilities, particularly in higher education. Roberts, who contracted polio and was paralyzed from the neck down at 14, defied expectations to become the first wheelchair user to attend the University of California, Berkley. His efforts started a movement that continues to champion accessibility, inclusivity, and empowerment in higher education. Inspired by this kind of education activism, guest Baya Clare tells us about their debt to Ed’s work and their own disability advocacy.

Ed Roberts is a towering figure in the history of disability rights. His advocacy challenged perceptions and created opportunities for people with disabilities, particularly in higher education. Roberts, who contracted polio and was paralyzed from the neck down at 14, defied expectations to become the first wheelchair user to attend the University of California, Berkley. His efforts started a movement that continues to champion accessibility, inclusivity, and empowerment in higher education. Inspired by this kind of education activism, guest Baya Clare tells us about their debt to Ed’s work and their own disability advocacy.

People in the disability advocacy community have probably heard the name Ed Roberts. Ed is known as the Father of Independent Living for his accessibility work in California and later across the US. As someone who became disabled in midlife, I didn’t learn about him until recently.

Ed contracted polio as a young teen and used an iron lung and a wheelchair. When he wanted to go to college, he decided to go to the University of California at Berkeley and study political science. At that time, the university had no accommodations for students with disabilities, and the state would only aid students they thought were employable after graduation. Ed was not deterred. With the help of his family and supporters, he fought for his right to attend. He earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree — paving the way for other students with disabilities to access higher education. Independent Living Roberts’ activism didn’t stop there. In 1972, he led the Independent Living Movement. This groundbreaking movement provided support services and advocacy for people with disabilities, empowering them to live independently and participate fully in society.

Roberts won a McArthur Genius Grant in 1978 and, along with Judy Heumann and Joan Leon, co-founded the World Institute on Disability. His efforts, along with the work of many others, opened the way for the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. He died in 1995, and his wheelchair is now at the Smithsonian. We commemorate his life and work each year on January 23.

Due to the work of Ed Roberts and other activists, colleges and universities no longer deny admission to people with disabilities, but barriers do still exist.

A few years ago, I took a required class for a program at a local university. It was at a time when I was becoming more disabled, and mobility was an increasing challenge. The class was in a beautiful, 100-year-old building that, though it had a ramp and thus technically met the building code for accessibility, was still an accessibility nightmare. I struggled each week with ice and heavy doors until I cracked some bones in both feet and couldn’t manage it anymore. About the fourth or fifth week, I requested to attend by video link, which the professor agreed to. (This was before arrangements like that were as common as they have become since the pandemic.) The department head, however, objected and sent me an email saying that the class was not set up as an online course. I’d have to drop it if I wasn’t going to be able to get there in person.

I sent an email to the campus Disability Office explaining the situation. I never heard more about it, except for a message from the disability folks saying they had contacted the department and worked it out. I was able to successfully finish the course by video link. The following semester, a for that program was scheduled in a much newer, more accessible building. I was grateful for the advocacy and help of the Disability Office and the quiet, competent way they supported me so I didn’t have to manage alone. They also educated the people in that department about disability and access in a way that helped them grow in understanding and made it easier for future disabled students.

The fact that there is a Disability Office on college campuses is due to the efforts of persistent people like Ed Roberts and his fellow student activists at Berkeley in the 1960s, who often had to struggle alone. I am mindful of and grateful for their hard work and perseverance in making the place more open for people like me. The work isn’t finished, certainly. People still encounter barriers on campus and in many other places, and Roberts’ legacy continues to inspire generations of activists and advocates in the disability rights movement. His courage, determination, and vision have helped to create a more inclusive and accessible society for people with disabilities. My experience shows that it is better than it once was. In other words, we can’t rest, but thanks to Ed Roberts and all the other persistent activists and allies, there’s hope, and we must keep working at it.